By Patrick R. Riccards

“NO ITALIANS ALLOWED — On May 28, 1888, council passed a resolution to the effect that parties receiving the contract for paving E. Washington St. shall bind themselves not to employ any Italian labor.”

That was from a newspaper article that I have carried with me since 2016. The news was the result of vitriol that claimed that, as the 20th century was approaching, Italian-Americans were here to steal our jobs, and were dark, swarthy, and could not be trusted.

For as long as I can remember, my positionality has been focused, first and foremost, on being both Italian-American and Catholic. Growing up in Northern New Jersey, most of my middle school friends were the same: young men that I served an altar boy with and kids whose last names ended in vowels (my own family surname was Ricciardelli until my grandfather legally changed it in the 1950s).

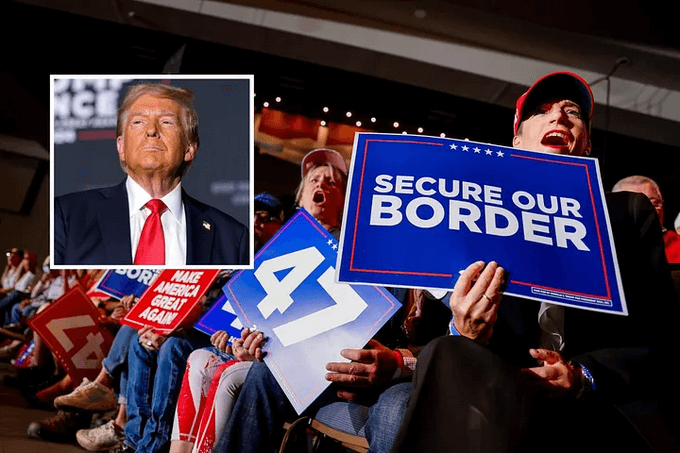

So why did I start carrying that clipping around? And why do I continue to do so? Almost a decade ago, I noted that many of those I grew up with, with whom I share positionality with, were strident foes of immigration. They were regularly railing against “those illegals” who are coming into our nation and stealing jobs from hard-working Americans (though to this day, I’m unsure if they know anyone who has lost a job to an undocumented immigrant). I started sharing the clipping on their social media pages, reminding them that the language they now use was the same language used to keep our great-grandparents out of our communities and out of gainful employment.

As a historian, I’m constantly amazed at how little we know about what comes back to us. The original “Make America Great” was the campaign slogan of Democratic President Woodrow Wilson, who is now best known for his rampant racism and misogyny, who viewed the racist The Birth of the Nation film at the White House. We don’t realize that not all of our Western European ancestors entered this nation legally through Ellis Island, as we’ve now romanticized in The Godfather. We don’t appreciate that our great-grandfathers came to this country because they didn’t have two Italian lira to rub together at the time, coming to our “teeming shore” to take on the jobs that many natural-born Americans simply didn’t want to do during the Industrial era. We don’t appreciate that the KKK set up camp on Long Island a little over a century ago largely to ensure that the Italians, the Irish, and the Jews didn’t make their way out of NYC into the beloved suburbs.

And I was equally amazed, discouraged, offended, and horrified when I saw the latest PRRI American Values Survey, which found that one-third of Americans say that undocumented immigrants are “poisoning the blood of our country”–the same language used against my great-grandfathers more than a century ago.

Those who share these views aren’t all who we think they are. While 61% of Republicans agree with that statement, so do 30% of Democrats. While 60% of white evangelical Protestants agree, so do 46% of white Catholics and 27% of Hispanic Catholics.

As a nation, we have clearly drunk the Kool-Aid when it comes to the negative impact of immigration and migrants. Forget that all of us, save for Indigenous Americans, are descendant of immigrants. Forget that many migrants are doing the sort of back-breaking labor that most of us would never want to do. Forget that we’ve watched this movie before, only with our own people portrayed as the villains.

For years now, I have publicly advocated that we all are entitled to hold our own beliefs and speak our own words, no matter how offensive or hate-filled those thoughts and words are. The U.S. Constitution guarantees it. But those rights do not make it permissible to threaten or physically harm others because of our personal beliefs. We all have an obligation, though, to ensure that those beliefs are educated by facts, not manipulated by propaganda.

As the father of two Latino young adults, I can say that my son and daughter are emblematic of the American dream. Nothing about them, their words, or their deeds is “poisoning the blood” of America, particularly when the majority of their blood is actually of the indigenous Mayan variety.

As an American, I can say that we should be collectively mortified by how casually we can now agree with a statement penned in the original German by Adolph Hitler, who wrote in Mein Kampf that “all great cultures of the past perished only because the originally creative race died out from blood poisoning.” But then, we should be even more angered that 20% of Gen Z American voters now believe that Hitler had “some good ideas.”

We all must be mindful that hateful thoughts beget hateful words. Hateful words beget hateful actions. Hateful actions beget hateful policies. And hateful policies beget hateful violence. While I will continue to defend one’s right to think, believe, and speak however they want, no matter how offensive, I also believe we all have the right, and the responsibility, to counter those thoughts and words with truth, with reason, and with sunshine.

Following the Constitutional Convention, Benjamin Franklin was asked by a newly minted American what the conveners had given us, a new nation. Franklin’s response: “A republic … if you can keep it.”

For the first time in modern history, we must begin asking if we are indeed capable of keeping our republic, our diverse representative democracy. Misinformation threatens our republic. A failure to understand and appreciate our history, whether that of our family or our nation, threatens our republic. And failing to speak truth to power threatens our republic.