By Patrick R. Riccards

Our nation has never been more divided than it is today. We see it in our politics. We see it in our schools. We see it in our social services. We see it in our media. We see it in our communities. And as those differences grow, we see it in the intensity of the responses and actions to them.

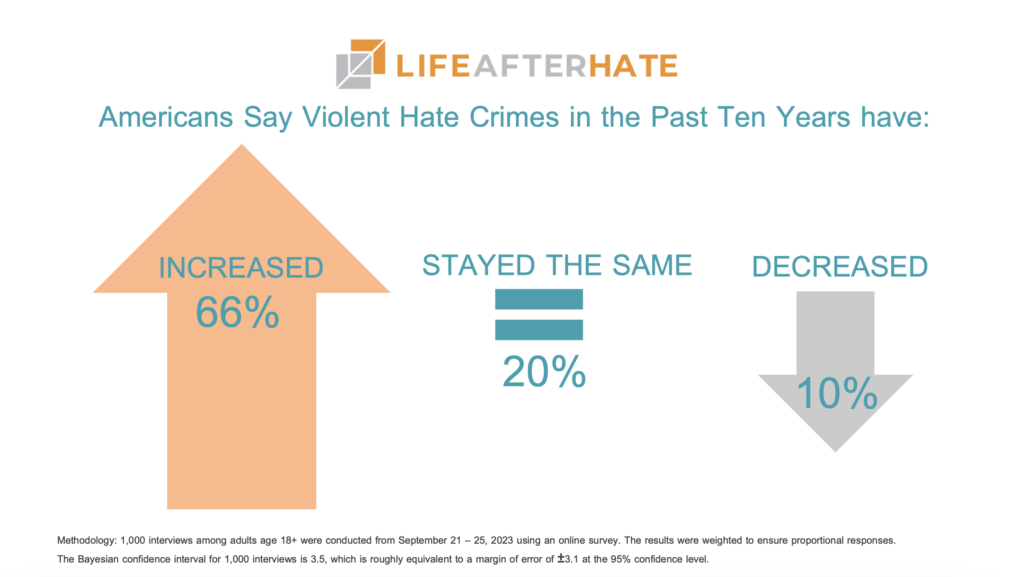

There is one thing we seem to agree on, though. In a new national survey, Americans overwhelming recognize the growing impact of violent hate crimes in the United States, with 66% agreeing such crimes have increased in the past decade, and only 10% saying the number has decreased.

In a survey conducted by Lincoln Park Strategies for Life After Hate, we see some startling trends, including the impact of ideology-based hate in our society. When it comes to the “flavor” of hate crimes we are experiencing, no demographic seems to be immune.

Only 8% say acts of violent antisemitism targeting the Jewish community has declined.

Only 8% believe we’ve seen a dip in hate crimes focused on Muslims.

Only 7% of Americans believe hate crimes against Asians have decreased.

Only 9% feel there has been a decrease in hate crimes targeting the Black community.

Only 9% feel hate crimes targeting Hispanics have declined.

And only 11% believe hate crimes against Christians have decreased, while 12% believe crimes targeting the White community have declined.

And we would be right. The statistics tell the same story. According to the latest FBI statistics released just yesterday, hate crimes continue to increase, with a “record-breaking” 11,643 hate crime incidents in 2022.

According to the latest data from the Anti-Defamation League, there were 3,697 documented incidents of antisemitism in the United States, the highest number ADL has seen, by far, this decade. From just 2021 to 2022, there was a 20% jump in such incidents.

Yes, we would like to believe that violent hate crimes are rare in the United States, but that is increasingly not the case. And Americans are now recognizing that. More than two in three surveyed (68%) say that violent acts of hate should be considered domestic terrorism.

In years past, we’ve been reluctant to believe that the violent extremism committed by our fellow Americans rises to the level of terrorism. But times have changed. Not only do we see that those living in border states and those who identify as Democrat overwhelming believe (80% each) violent extremism is domestic terrorism, the majority of those living in rural communities and those who identify as Republican share that belief (58% each).

Acknowledging that we have a problem is the first step. Let there be no mistake, no corner of civil society is immune from ideology-based acts of violence. Hate crimes continue to rise, and we must now see it for the dangerous problem that it is. Ideology-driven violence is domestic terrorism, and we know it.

Taking that first step, though, does not mean we have successfully addressed the problem. Not only must we recognize the threat that hate-based ideology plays in our society, but we must also recognize there are steps we can, and should, take to begin to reduce violent hate crimes in our communities and our society.

While almost half (48%) of those surveyed believe that those who have been convicted of violent hate crimes will likely not change their thinking or actions, violence intervention groups like ours know otherwise. For more than a dozen years, we have been building safer communities by helping individuals exit violent far-right extremist groups and online hate spaces. As the nation’s leader in such work, we are committed to preventing hate-fueled violence through licensed social services, peer mentor interventions, and public education.

To be clear, the work is hard. Very hard. For those who question whether change is possible, they likely do so because they can’t conceive of the time and effort required both of those exiting violent extremism and those professionals and peer advisors who are committed to helping them. But it is possible. Possible when licensed mental health professionals and social workers are part of the process. Possible when there are clear ethical and professional standards in place. Possible when we are honest about the time and effort such work takes. Possible when those seeking to exit violent extremism take responsibility for their past actions. And possible when we believe that no one should be judged by their worst day, if they are willing to take accountability for it.

Violent extremism stands as a clear and present danger to this country and to the vast majority of its people, regardless of the label it wears. White supremacist. White power. Antisemitic. Misogynist. Anti-LGBTQ+. Anti-immigrant. Anti-Muslim. Anti-Asian. Anti-government. Accelerationist. They are all hate-based ideologies that physically manifest themselves into violence too often, in too many communities, against too many Americans.

The latest data speaks to the seriousness of the problem and the surprising reality that we, as a nation, agree on the growing threat violent extremism plays. And a decade-plus of work from Life After Hate shows us a path forward, one that embraces the belief of compassion with accountability.

We may not yet believe that one can disengage and deradicalize from violent extremism, but groups like ours demonstrate that change and improvement is possible. We can build a safer community if we recognize violent extremism as the public threat it is and provide licensed, professional social services to those brave enough to take accountability for their pasts and seek to change their hateful ways.